Commodity Supercycle and Risks to Energy

What is a commodity supercycle? Are we in one? Energy vs Industrial Metals supercycles. How does the November US election affect a potential energy commodity supercycle?

Commodities have some huge upside since 2021. As a basket of goods, using the S&P GSCI Index, commodities are up 26.4% as of writing. Precious metals making the biggest gains: gold is up (47%) and silver is up (34%). Brent Crude is up 45% and WTI Crude up 62.3%. While natural gas lags behind, being down 32.3%.

The question is are these increases a result of demand recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic or the start of another commodities supercycle.

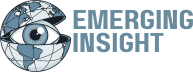

A global commodities supercycle is defined as sustained increase in the price of commodities worldwide that lasts for more than five-years. We’ve been through a couple of them in the last few decades, including the one beginning in 2001 after China’s admittance to the WTO and the one immediatley following the 2008 financial crisis. In these years commodity prices stayed significantly above their long-term trends. The Bank of Canada in a recent paper defines these supercycles as the Commodity Price Index deviating from its long-term trend by more than 10%. It identified four bull-cycles between between 1990 and 2015, using this methodology.

Goldman Sachs was the first institution to call the start of a commodities supercylce, in late 2020. Their then Head of Commodities Research, Jeff Curie, has remained committed to that thesis despite ranging oil prices and a slowdown in global economic demand since 2022.

The main pusher of supercycle is likely a combination of global economic recovery and underinvestment in supply in key commodities.

This is espeically pertinent as governments and private companies in the West look towards the ‘green transition’ which will require key metals such as copper, lithium, and cobalt in new infrastructure and modern technologies.

Although no two supercycles are the same, they are driven by a similar underlying driving force - this analysis reflects this. Supercycles are generally preceded by a sustained period of supply-side underinvestment, lacking spare-capacity, and a draw-down of inventories.

Underinvestment is almost a feature of commodity supplies. Mining and drilling companies have their valuations driven by the spot prices of the commodities they supply. In a different market this would allow them to quickly respond to market demand, as their valuations increase firms can offer more in collateral and as such borrow more. However, supply-side projects for energy and mining companies are often huge and have massive lead times. This makes the super-cycle almost structural with demand shocks.

According to the S&P, it takes an average of approximately 16 years for a mine to go from discovery of a deposit to startup. While the entire process for oil rigs takes anywhere from 18 months to 5 years. Even expansion of existing projects takes a lengthy period of time. This means that these companies will always struggle to respond to demand. This role is often fulfilled by inventories, but when they are a drawn-down from increasing demand or geopolitical situations then there is a no other way for prices to stay stable. Thus starting a bullish supercycle.

Schroders estimate that capital expenditure in oil and gas and the global mining sectors has fallen by around 40% since 2011. While CapEx in the copper industry, a crucial metal for the green transition, declined by 44% between 2012 and 2020.

Metal Supercycle

The push for the ‘green transition’ will be the demand shock that starts the supercycle in metals. It can be argued that this shock has already occured, with the biggest economic entities having announced their plans - and they have tight timelines. China’s latest five-year plan to Europe’s Green Deal to US Inflation Reduction Act.

In June 2022, China released the 14th Five-Year Plan (FYP) on Renewable Energy Development (2021–2025), a comprehensive blueprint for further accelerating China’s renewable energy (RE) expansion. The plan targets a 50 percent increase in renewable energy generation (from 2.2 trillion kWh in 2020 to 3.3 trillion kWh in 2025), establishes a 2025 renewable electricity consumption share of 33 percent (up from 28.8 percent in 2020), and directs that 50 percent of China’s incremental electricity and energy consumption shall come from renewables over the period 2021–2025. Achieving the targets in the plan will reduce up to 2.6 gigatons of carbon emissions annually (equivalent to almost one-fourth of China’s total carbon emissions in 2020).1

The Biden Administration’s Inlation Reduction Act (IRA), provides tax incentives, credits, and expanded grants to households, companies, state and local governments, and non-profits to invest in clean energy.2

The European Green Deal is a package of policy initiatives, which aims to set the EU on the path to a green transition, with the ultimate goal of reaching climate neutrality by 2050. The package includes initiatives covering the climate, the environment, energy, transport, industry, agriculture and sustainable finance – all of which are strongly interlinked.3

All of this government policy is the catalyst for a new a new supercycle. Outside of China and the countries proposing these policies are also not helping themselves. In the U.S., despite Biden saying that new mines are a priority, new projects have found themselves embroiled in legal and enviromental challenges, struggles to navigate local bureaucracy, and opposition from activists (ironically often the same ones advocating a “Green New Deal”).

The EU is no better. Although they are looking to introduce new legislation that aims to make opening new mines easier.4 But with the EU’s record on overly-complex legislation and a population of vocal activists, like in the US, it’s hard to see how effective their efforts will be.

For metals this will lead to an extended supercycle, more than the 5-year minumum and more towards the 10-15 year mark or further as mines struggle to open.

Energy Supercycle?

It’s harder to see if energy (especially in traditional fossil fuels) will follow a similar supercycle to metals.

However the same drivers that are stopping the production of new mines in the US and the EU is also causing underinvestment in oil and gas and with far more fervor. More so what’s causing the underinvestment is the prevailing narrative of ‘peak oil’. Yet, ‘peak oil’ is still far off.

The IEA is the main purveyor of this narrative. “Currently, oil and gas sector spending of some $800 billion each year is double what is required in 2030 on a pathway that limits global warming to 1.5 C.”5 Yet the fact of the matter is that many countries are going to miss these goals and the developing nations of world are going to ignore entirely, even if they pay some lipservice at UN meeting.

Despite widespread predictions of electric vehicles (EVs) displacing oil demand, their increasing adoption has not led to a significant reduction in oil consumption. Norway, which has the highest EV penetration globally, serves as an intriguing case study. Even as the share of EVs in new auto sales soared from 3% to 80% over a decade, Norway’s oil usage has not collapsed. In China, the largest EV market in the world, oil demand rose 50% as EV penetration went from less than 1% in 2012 to over 20% today.6

According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), the petrochemical sector is projected to be the primary driving force behind global oil demand. Jet fuel and heating for industrial and residential users arestill major areas of oil demand. These are far less penetrated by green technology, and in the case of jet fuel there exists no economic alternative.

The global appetite for oil is on track to hit an all-time high by the end of this year. Stronger-than-expected global GDP growth and a structural improvement in jet fuel demand have driven this pace. The U.S., China and Europe combined account for half of global oil consumption. Demand in the rest of the world is still 1 million barrels a day below 2019 levels, suggesting that there is room for growth.7

If we choose to ignore the IEA’s analysis as having been captured by the prevailing narrative of ‘peak oil’, then we’re looking at underinvestment similar to the metal market but not at the same scale. The extra demand for oil isn’t there but the underinvestment is.

Thus we can conclude that there may be two seperate supercycles. One for metals that remains high for the next decade and one for energy that will last for a far shorter period of time.

Risks to Demand: The China Question

It’s a possibility that demand spike required for the supercycle to occur and be maintained may be subdued by a weak China. Both OPEC and the IEA cut their demand forecasts, although their is still a large gap between them. Both organisations say weak demand from China is the reason.

Post-pandemic saw Chinese oil demand jump to 15 to 16.6 million barrels per day, but which is now mostly exhausted. Jet fuel demand is the one bright spot, with foreign passenger flights still not back to 2019 levels.

Robin Mills, writer of ‘Energy this Week’ at the www.thenationalnews.com, suggests that general economic weakness is another key contributor. “This is a mix of cyclical and at least semi-permanent features. Growth of 4.7 per cent in the second quarter was below target, with the puncturing of the real estate bubble and more barriers to exports.” Slowing construction and freight cuts diesel demand, even though the manufacturing sector still hums along. Further, China’s working age population peaked in 2015, and is projected to be half of that peak by the end of the century.

There is also a technological factor specifically for oil demand. China has been switching out their old trucking fleets for new ones that run on LNG, saving 220,000 barrels per day last year. An expected global glut of LNG from around 2026-2027 will further encourage this substitution.

Overall weak energy demand in China, and especially a China where oil is being substituted for other energy sources, will supress global oil prices. However, the increasing use of natural gas not only in China but in the developing world as a clean energy source (as in it burns clean and doesn’t cause the awful pollution), may see price trends in oil and natural gas split in any supercycle.

Supply Risk: The US Election

We won’t be focusing on the usual trouble in the Middle-East in this week’s edition. The risk there will have some effect on prices but it is unlikely such price effects will be permanent.

What may effect global supply is the policies of the two candidates running for the Presidency of the United States, stated policies or otherwise.

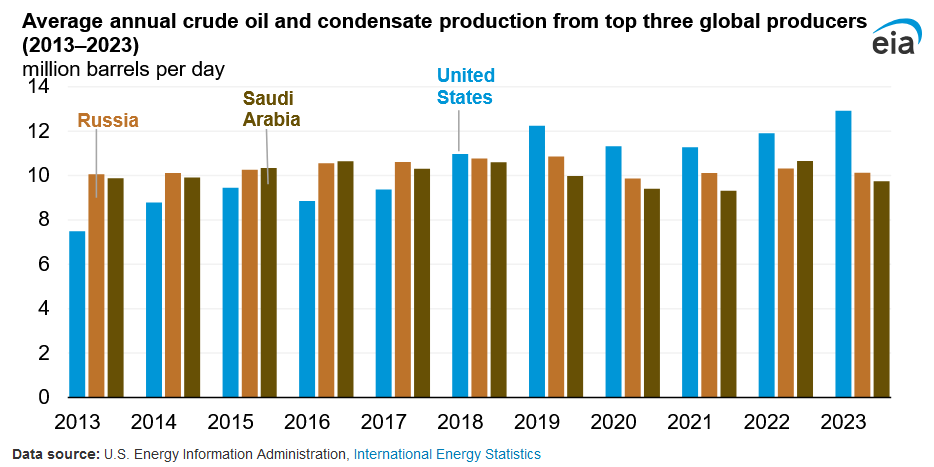

The US now produced more crude oil than any country, and has done so since 2018. After peaking at 9.6 million b/d in 1970, annual U.S. crude oil production flattened and then generally declined for decades to a low of 5.0 million b/d in 2008. Crude oil production in the United States began increasing again in 2009, as producers increasingly applied hydraulic fracturing and horizontal drilling techniques, and has increased steadily since. The only exception to U.S. production growth since 2009 was in 2020 and 2021, when demand and prices decreased because of the economic effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. In recent years, crude oil production in the Permian Basin (in western Texas and eastern New Mexico) drove the increases in total crude oil and natural gas production in the United States.8

The energy policies of the next administration will have massive effects on global energy prices. Under the Kamala Harris situation, we predict that US supply will be hampered, exacerbating the length of any energy commodity supercycle. Under the Donald Trump situation, we predict an expansion of US supply and the continuation of US as a net energy exporter.

Harris has been purposeful vague on her energy policy so far, it is still early doors but with the November not far away we’d expect to hear something soon. Yet the activists aren’t disuaded. Climate groups this week announced a $55 million advertising campaign to support the Harris ticket. One reason why Harris may be vague as to her views on US energy policy and fossil fuels is that it might not sit well with the independent voter.

In 2019, Harris positioned herself to the left of Biden, calling for a fracking ban and a tax on carbon pollution, as well as changes to federal dietary guidelines to encourage less meat consumption. She did not advocate those positions once she became Mr. Biden’s running mate and then vice president. A spokesman said Ms. Harris no longer supports a fracking ban. As California attorney general from 2011-2017, Harris won multimillion-dollar settlements with oil majors Chevron and BP over pollution violations from underground fuel storage tanks. Stephen Brown, an energy consultant and former lobbyist with Tesoro, who had a large refining footprint in California, said Harris had not engaged constructively with the oil and gas industry during her years on Capitol Hill from 2017-2021.9

We know Harris’ position, even she states otherwise or doesn’t state at all in her campaign. This position obviously increases the risk of her adminstration going after fossil fuel production in the country. Whether its carbon taxes which will limit investment, or the refusal of licenses all together. Any decrease in investment will exacerbate a potential energy supercycle.

Trump’s position is entirely different. He’s made it clear he supports a significant shift away from the current energy policy of the Biden administration. If Trump repeats his “America First Energy Plan” of his previous term, the US would be looking at sweeping deregulation of the oil and gas industry and increasing licensing of public land for drilling purposes.

Although their are other areas of Trump’s policy to be worried about on the macro level (such as tarrifs and trade with China), it’s unlikely Trumpian policy would exacerbate any energy supercycle, but instead likely reduce it.

Overall we can conclude the following:

We’re likely in the commodity supercycle

There are two supercycles, one for metals (precious and industrial) and one for energy commodities (crude oil and natural gas)

The metals supercycle will last far longer than any energy supercycle

Any potential energy supercycle faces risks to exacerbation by the a Harris administration.

Commodities are likely to trade in a higher band, in both real and nominal terms, for the next few years. This analysis specifically applies to industrial metals and potentially energy commodities. It’s likely that the precious market will follow suite as they usually do during supercycles but the drivers of gold and silver are different.

https://www.efchina.org/Blog-en/blog-20220905-en

https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/jy1830

https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/policies/green-deal/

https://www.highnorthnews.com/en/new-eu-legislation-make-opening-mines-europe-easie

https://www.spglobal.com/commodityinsights/en/market-insights/latest-news/oil/112323-iea-warns-of-oil-gas-sector-over-investment-risk-under-net-zero-push

https://www.morganstanley.com/im/en-us/individual-investor/insights/articles/oil-unrestrained-underappreciated-and-underinvested.html

ibid.

https://www.eia.gov/todayinenergy/detail.php?id=61545

https://www.reuters.com/world/us/harris-energy-policy-is-strategically-ambiguous-her-aides-say-2024-08-14/

An excellent article, l learnt so much. I need to spend more time on commodities, it's a real blind spot for me but l consider reading this a step in the right direction. Well written, well referenced, good work all round, Cam.